Back in 2015 I told the story of Anders Anderson who, among other things, owned and managed Oak Ridge Cemetery and erected the magnificent Oak Ridge Abbey mausoleum:

In my article about Anderson I described the Oak Ridge Abbey in great detail so I will not repeat myself here. In this article I want to tell the story of the man who designed and constructed the Abbey, noted architect Joseph J. Nadherny.

Joseph Jerome Nadherny, Jr. was born August 14, 1891 in Chicago, Illinois to Joseph J. Nadherny Sr. (1856-1936) and his wife Anna nee Kreji (1864-1953). Josef Nadherny and Anna Kreji married in Chicago on August 1, 1885. Josef (Joseph) Nadherny was a tailor by trade. In addition to Joseph Jr., Joseph and Anna had five children: Florence (1887-1970), Victor John (1893-1982), Clara (1897-1983) [Mrs. Charles Phillimore], Rose (1902-1994) [Mrs. Carl A. Berg] and Pauline (Dates Unknown).

I was unable to locate the Nadherny family in the 1900 US Census, but the 1910 US Census shows the family living at 1845 S. Millard Avenue in Chicago.

The family consisted of 55 year-old Joseph, 46 year-old Anna, 20 year-old Florence, 18 year-old Joseph Jr., 16 year-old Victor, 13 year-old Clara, and 9 year-old Rose. Anna said she had given birth to six children, 5 of which were still alive in 1910. Joseph Sr. said he was a Cutter and Tailor by trade. Joseph Jr. was a "Draughtsman in Architecture." The family owned their home free and clear. Joseph and Anna reported their birthplace as "Austria-Bohemia."

Joseph Nadherny the younger never referred to himself as "Junior," so for the remained of this article when I am referring to Joseph Nadherny I will be referring to the architect, not his father unless otherwise indicated.

Joseph Nadherny graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture in 1916.

It was also reported that Scott Dyer had "fallen in love" with South Florida and regretted that it had gotten so much bad press. Dyer further said that he soon hoped to relocate to Fort Lauderdale and open an office of Dyer & Nadherny down there.

|

| 1845 S. Millard, Chicago |

The family consisted of 55 year-old Joseph, 46 year-old Anna, 20 year-old Florence, 18 year-old Joseph Jr., 16 year-old Victor, 13 year-old Clara, and 9 year-old Rose. Anna said she had given birth to six children, 5 of which were still alive in 1910. Joseph Sr. said he was a Cutter and Tailor by trade. Joseph Jr. was a "Draughtsman in Architecture." The family owned their home free and clear. Joseph and Anna reported their birthplace as "Austria-Bohemia."

Joseph Nadherny the younger never referred to himself as "Junior," so for the remained of this article when I am referring to Joseph Nadherny I will be referring to the architect, not his father unless otherwise indicated.

Joseph Nadherny graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture in 1916.

He was not going to let any grass grow under his feet. When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917 he was already working for himself:

Joseph Nadherny served in the US Army during World War I. He enlisted on June 28, 1918 and was discharged April 30, 1919. He served as a Private in the headquarters of the 13th Field Artillery Regiment. By that time the Nadherny family had relocated to suburban Oak Park, Illinois. Their new address as reported by Joseph was 707 Home Avenue, Oak Park, Illinois:

|

| 707 Home Avenue, Oak Park, Illinois |

The 1920 US Census shows the Nadherny family living at 707 Home Avenue in Oak Park which for some reason the census calls "Wesley" Avenue. Wesley Avenue in Oak Park is actually six blocks east of Home Avenue. The census lists the family as Joseph (59), Anna (56), Florence (30), Joseph Jr (28), Victor (25), Clara (22) and Rose (17). Anna Nadherny could neither read nor write, which was not all that unusual for women of this era. They also reported that they owned their home, and that they had a mortgage as did most Americans. Both the elder Joseph and Anna were naturalized American citizens.

Joseph Sr. was a tailor, as was Victor. Joseph Jr was, of course, an architect. Clara was a stenographer in a bank. All of the family reported that they spoke English. Yes, the Nadhernys had become a typical American family.

Chicago was a bustling thriving city during the boom years of the 1920s and Joseph Nadherny was right there to build it. On July 02, 1922 the Chicago Tribune announced that Joseph Nadherny had drawn up plans for a $60,000 temple for the Independent Order of Odd Fellows at Oak Park Avenue and Windsor Street in Berwyn:

The building is still there today:

3242 Oak Park Avenue, Berwyn, Illinois

Later in 1922 Joseph Nadherny decided to stop going it alone and teamed up with noted architect Scott C. Dyer (1889-1947) to form the firm of Dyer & Nadherny. Dyer was know for designing Masonic Temples and Nadherny for designing Odd Fellows Halls so it seemed to be a good match for the two. Nadherny moved into Suite 1531 in the First National Bank Building which had already been occupied by Dyer since 1917.

The 1922 University of Pennsylvania alumni directory shows that Nadherny's architectural office was at 1531 First National Bank Building in Chicago.

The November 2, 1924 edition of the Chicago Tribune made a happy announcement:

On October 24, 1924 Joseph Jerome Nadherny married Helen Amelia Storkan. Helen Storkan Nadherny (1898-1987) was born in Chicago to James Storkan (1871-1964) and Marie Emilie Kralovic (1874-1963). James Storkan was a real estate attorney and banker. Here is a photo of Helen's parents, James and Marie Storkan:

In addition to Helen, the Storkans had three other children: Robert (1896-1976), Julie Marie (1901-1987) [Mrs. George A. Basta], and Pauline (1905-1988) [Mrs. Stephen E. Boback].

1925 was a banner year for Joseph J. Nadherny. On August 17, 1925 Joseph and Helen's daughter Jeanne Helen Nadherny (1925-2013) [Mrs. Norbert Buenik] was born and then on December 6, 1925 the Fort Lauderdale (FL) Sunday News announced that Dyer & Nadherny's plans for a $500,000.00 Hotel Riviera in Fort Lauderdale, Florida had been approved:

The article also mentions that Dyer & Nadherny were currently working on plans for the Michicago Field Club, a 500 room hotel in Benton Harbor, Michigan, and had completed (in 1922) plans for the Golfmore Hotel in Grand Beach, Michigan, said to be the "finest resort hotel in the north."

But business was booming for Dyer & Nadherny in Chicago. After his European trip in 1924, cemetery owner Anders E. Anderson approached Joseph Nadherny about designing a mausoleum for his Oak Ridge Cemetery in the Chicago suburb of Hillside, Illinois. Anderson didn't want a mausoleum that looked like others that had been built in Chicago, or even like the mausoleum in the cemetery next door, Glen Oak. So what did Joseph Nadherny produce for Anders Anderson? The Oakridge Abbey Mausoleum - the only compartment mausoleum built on the cruciform plan, where brilliant wide white marble steps lead to the columned entrance, whose massive doors of solid bronze are works of art. The Abbey is also said to be "a poem in marble and bronze."

Furthermore, Oak Ridge Abbey is one of the few mausoleums that has the crematorium right inside the same building. This is not uncommon today but in the 1920s was unheard of.

When the Bella Morte website visited Oakridge Abbey, here's what they said:

Upon entering the Abbey, one encounters columbaria with glass-front niches just outside the chapel. The chapel itself is captivating, resting as it does beneath an expansive arch of stained glass which admits the soft glow of natural, filtered light. Edgar Miller's beautiful art glass "Lady of Eternity" keeps watch over her domain from her place behind the marble altar. Lining the nave of the chapel are large stone pillars beyond which lie numerous interment chambers, each comprising ten burial vaults.

The remainder of the Abbey features red-carpeted marble hallways flanked on each side by gated crypt rooms, our favourite of which is that belonging to Mr. and Mrs. Otto Pelikan. Inside, a bare-breasted marble faerie stands delicately before colourful stained glass windows, her raised left hand posed to open a small urn.

One either side of her rest the ornate tombs of Ruth Lila and Otto Pelikan. Above them, etched letters gilt in gold proclaim "Seventh Heaven." Indeed. We wish nothing less for this obviously loving couple. Incidentally, someone tends this tomb with care as each time we have visited, a fresh red rose has been laid atop each Pelikan crypt.

Bella Morte concluded, "When in Hillside, Oakridge Abbey simply must be included in your list of places to see."

Other architects who designed mausoleums such as Sidney Lovell or Cecil Bryan did not stop at designing just one. Lovell is purported to have designed fifty-six community mausoleums; we can identify forty-nine. Cecil E. Bryan is credited with designing eighty community mausoleums. Unlike Lovell or Bryan, Joseph Nadherny seems to have only designed one: Oakridge Abbey.

His architectural career did continue, however, even if he did not design any other community mausoleums. On February 24, 1929 the Chicago Tribune announced that Dyer & Nadherny designed a four story factory building for the Triner Scale and Manufacturing Company at Twenty-first Street and Fairfield Avenue in Chicago:

The building is still standing:

But Dyer & Nadherny were not finished yet. On August 4, 1929, the Tribune announced that Dyer & Nadherny had designed a 2,500 seat theater in Chicago on Ogden Boulevard at Menomonee Street which would be called "The Orient" (not to be confused with the Oriental Theater in downtown Chicago.)

The Orient theater - a 2,500 seat movie theater proposed for a site at Ogden boulevard and Menomonee street. Designed by Dyer & Nadherny, the structure is to be modernistic in feeling. Besides the theater, the building will contain stores and flats. The cost is estimated at $1,000,000. The United Theater Corporation of Illinois is owner.

Unfortunately it does not appear that the Orient Theater was ever built.

The 1930 US Census shows the Joseph Nadherny family living at 4851 West End Avenue in Chicago. A vacant lot occupies that space today. The family rented their apartment for $85.00 per month. The family consisted of 38 year-old Joseph, an architect in general practice, 32 year old Helen, their 4 year-old daughter Jeanne, 9 year-old nephew Benton Annerino, and 20 year-old cousin Marie Levey. Joseph told the census taker that he had served in the World War, that he was born in Illinois but his parents were born in Czechoslovakia, and that they did own a radio.

The Depression years were hard for all Americans and architects were no exception. During the 1930s Mrs. Joseph Nadhern's name appeared in print many more times than her husband. Mrs. Nadherny was involved in many Bohemian social and charitable organizations in Chicago. One example was when the Chicago Tribune reported on October 1, 1933 that Mrs. Joseph J. Nadherny was appearing in a one-act play 'About Face' for the Bohemian Women's Club with another woman of Bohemian ancestry, Mrs. Otto Kerner. Otto Kerner, a protege of martyred Chicago mayor Anton Cermak would go on to be elected governor of Illinois from 1961-1968.

Scott Dyer and Joseph Nadherny had not seen eye-to-eye for a long time. Dyer was more interested in South Florida; Nadherny was perfectly happy in Chicago. Things came to a head and the Chicago Tribune reported on October 6, 1935 that Dyer and Nadherny were parting company:

As mentioned in the article, Joseph Nadherny's office was now at 1518 West Roosevelt Road in Chicago, which was the building owned by the Bohemian National Building, Loan and Homestead Association. Townhomes occupy that site today.

In the 1930 US Census Joseph Nadherny told the census taker that he was an architect in general practice. He did not limit his expertise to only commercial properties, he was willing to design or redesign houses as well. Commercial building during the Great Depression had ground almost to a halt, so Nadherny took whatever architectural jobs that were available. We can see this in an article from the Chicago Tribune of August 15, 1937 when Nadherny gave advice about the remodeling of a house:

By 1940 the Depression was finally wearing itself out and things were looking better, but this was tempered by the rumblings of war. The war was already raging in Europe and the Far East. Thoughtful men knew that ultimately the United States would be drawn into the war again - just as it had in World War I.

The 1940 US Census taker came to the Nadherny home on April 12, 1940. Now the family was renting an apartment at 1517 North Austin Avenue in Chicago, for which they paid $100.00 per month. There were no relatives living with the Nadhernys in 1940 as there had been in 1930 - it was only Joseph, Helen and Jeanne.

Joseph was 48 years-old, he was an Architect in "Private Business." 41 year-old Helen and 14 year-old Jeanne were not employed. They had been living at the same address in 1935.

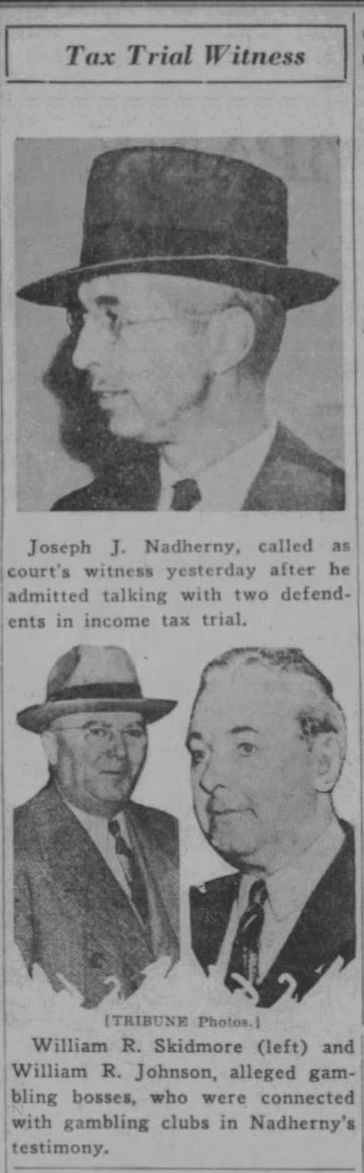

Things got a little more lively for Joseph Nadherny later in 1940 when he became involved in what was known as the "Club Western Trial." On trial was William R. Johnson and some of his associates. Johnson was an alleged gambling boss who was on trial in Federal Court for income tax evasion and his associates were co-defendants in the tax evasion matter. Johnson's lawyers attempted to reduce his tax liability by showing that William (Billy) Skidmore owned 1/2 of the Club Western, a gambling joint at 9730 S. Western Avenue in Chicago. An 8-story medical office building built in 1952 occupies that site today.

Joseph Nadherny was originally set to be a witness for the Defense. During 1938 and 1939, he had worked as an architect and construction supervisor for both Johnson and Skidmore. Nadherny had met Johnson through Skidmore.

Nadherny had been prepared to appear for the defense but when court convened on September 2, 1940 the Assistant US Attorney E. Riley Campbell said that he had just been told that on the previous Saturday night, that Nadherny visited the Bon-Air Club, a gambling establishment in Lake County, and talked with two of the defendants. He had further been informed that Nadherny discussed the matters at trial with the defendants. Campbell wanted Nadherny called immediately as a witness for the prosecution. This was allowed.

Campbell examined Nadherny who admitted that he had been at Bon-Air and that he had "casual talks" with two of the defendants Ed Wait and Andrew Creighton. "I met Wait first, at the bar," Nadherny testified, "and he told me that he thought that some of the testimony given last week (by William Goldstein) was false." Soon afterward, Nadherny said, he had met Creighton and their conversation concerned construction work at the Club Western. Nadherny had drawn up the plans for the gambling house there.

"We talked about the subject that Creighton had paid some of the money for extra work done on the club, and also the fact that Skidmore had paid a portion of the money for the place," said Nadherny. "Who brought up the subject?" asked Campbell. "I would say Mr. Creighton. He said something about my testimony and and I remarked that I never had mentioned the fact that Mr. Creighton had given me some money."

Under further examination Nadherny said he had received $2,500 at one time from Creighton, and that in all Creighton spent $6,000 as his share in the Club Western. When asked what the total cost of the club was, Nadherny replied "$22,000.00." Campbell asked further, "Who paid the money?" and Nadherny replied "Skidmore." Campbell: "In what form?" Nadherny: "Currency."

This was the first time, government attorneys said, that they had heard from Nadherny that Skidmore had passed out the money. Nadherny tried to explain that on previous occasions that he assumed the money had come from Johnson although it had been paid by Skidmore. Therefore, Nadherny said he had related previously that Johnson had paid the money, although it was Skidmore who had actually paid it.

"It was also the first time," prosecutors said, "that Nadherny had told of Creighton's share in the Club Western." Nadherny explained that by saying that the district attorney's office had never asked him about such an item.

Nadherny told in detail of his work at the Bon-Air Club. The cost of the work was $130,000.00. His fee was $7,800.00. Again Skidmore's name was brought out.

"How were you paid?" Nadherny was asked. "I received two payments," he replied. "I remember I mentioned the matter to Mr. Johnson, and he said to see Mr. Skidmore because he was going out of town. I saw Mr. Skidmore and he gave me $2,500.00. I got the balance from Mr. Johnson."

This seems to have been the end of Joseph Nadherny's involvement in this matter. Whether or not Nadherny's testimony made any difference we do not know, but the defendants were all convicted of tax evasion.

Joseph Nadherny's former partner Scott C. Dyer died in Fort Lauderdale, Florida on January 9, 1947. His body was returned to Chicago and buried in Graceland Cemetery.

In 1956 Joseph Nadherny had his sixty-fifth birthday. In those days most people were required to retire at 65 but people who were self-employed could continue working as long as they liked. Nadherny however decided that the time had come to enjoy life so he retired. Joseph and Helen Nadherny stayed in their apartment on Austin Boulevard in Chicago until 1969 when they moved to Pasadena, California.

Here is a photo of Joseph and Helen Nadherny from that time period:

In 1973 they moved from Pasadena to 2727 Miradero Drive in Santa Barbara, California to be closer to their daughter Jeanne, her husband Norbert and their two grandsons, Bert and Michael Buenik. There were also close to Joseph's remaining sibling, his sister Rose who lived in Laguna Hills, California.

Joseph J. Nadherny died in Santa Barbara, California on June 29, 1986. He was 94 years old. Here is his Death Notice from the Chicago Tribune of July 8, 1986:

Joseph J. Nadherny rests today in the magnificent mausoleum he designed, Oak Ridge Abbey in Hillside, Illinois:

Like Anders Anderson, Nadherny chose to be laid to rest in the magnificent mausoleum that he and Anderson had created.

When you visit Oak Ridge Abbey it would be appropriate to use for Joseph Nadherny the epitaph attributed to another famous architect, Christopher Wren:

"Si monumentum requiris circumspice."

"If you would seek my monument, look around you.''

May he rest in peace.