Prior to 1980 if you took a walk or drive along the Evanston lakefront you would have seen a small frame house at 1834 Sheridan Road:

Ultimately owned by and torn down by Northwestern University, the house was built in the 1880s by Lawrence O. Lawson, an old sea salt who became a legend in his own time. In 1880 he was appointed captain of the Evanston life-saving station, a position he would hold for almost a quarter of a century. Long forgotten today, Captain Lawson and his crew rescued over 500 souls from the treacherous waters of Lake Michigan.

Before we recall the bravery and skill of Captain Lawson and those Northwestern students who served as his crew from 1880 to 1903, let's see what we can "dig up" about Lawrence Lawson.

|

| 1834 Sheridan Road, Evanston, Illinois |

Ultimately owned by and torn down by Northwestern University, the house was built in the 1880s by Lawrence O. Lawson, an old sea salt who became a legend in his own time. In 1880 he was appointed captain of the Evanston life-saving station, a position he would hold for almost a quarter of a century. Long forgotten today, Captain Lawson and his crew rescued over 500 souls from the treacherous waters of Lake Michigan.

Lawrence Oscar Lawson was born Lars Oskar Eskilsson on September 11, 1842 in Kalmar, Sweden to Eskil Larsson (1813-1856) and his wife Johanna Carrie Sjogren (1817-1896). Lars had two sisters, Elise Marie Eskilsson (1851-????) and Hanna Julia Eskilsson (1854-1868). Little is know of Lars' early life except for one story he told about himself:

"At his old family home was a grist mill, and one day his love of the water caused him to fall into the mill stream. He was carried around the mill wheel, and his arm was permanently crippled. When he was fourteen years old his father died, and four years later the boy went to sea. In 1861 he came to New York. From there he shipped before the mast for three years, and was on the first vessel to sail into New Orleans after the capture of the city by Union forces."

The life-saving service at Evanston was established in 1871, as a response to several tragic shipwrecks off the shore of Lake Michigan. The most notable of these was the wreck of the steamer Lady Elgin in 1860. Over 300 passengers lost their lives when the Lady Elgin collided with a lumber schooner a few miles northeast of Evanston. Prompted by this disaster and others, concerned citizens pleaded for a life-saving station that could assist ships in distress.

Consequently in 1871 the U.S. Navy furnished Northwestern University with a 26 foot long lifeboat to be directed and manned by the students. A red-brick life saving station was built in 1876 on the site of the present day Fisk Hall. During the early years the captain and crew were drawn from among the Northwestern students. At the annual graduation exercises, the life-saving boat was handed down by the seniors to the junior class and a new captain was chosen. As time went on however, it was felt that the work of the student crew would be more effective if a person with more experience and maturity filled the captain's role.

We do not know when Lars Eskilsson Americanized his name but several things had changed after he returned to New York in 1864. This time he decided to follow the herd and "Go West." In December of 1864 the newly named Lawrence Oscar Lawson left Buffalo, New York on the schooner "Tanner" headed for Chicago.

He liked what he saw around Chicagoland so he decided to settle here. He bought some land in Woodlawn and took up the occupation of a fisherman. He did not entirely forsake a seafaring life, however, and for two years he sailed the Great Lakes as a sailor before the mast with Captain Lindgren.

In 1869 Captain Lawson moved to beautiful Evanston, Illinois and continued the life of a fisherman, occupying a shanty near the Davis Street pier. In 1876 he married the former Petrine Wold (1855-1941) from Norway. Right after their marriage the newlyweds moved to Ludington, Michigan but by 1878 they returned to Evanston where they would remain for the rest of their lives.

On July 19, 1880 Lawrence Lawson was appointed to be the keeper, or captain of the life-saving station at Northwestern. A sailor of life-long experience, he was chosen to make seamen of the eager but inexperienced students. Just shy of his 38th birthday, he also fulfilled the requirement for "maturity" that the job required,

He liked what he saw around Chicagoland so he decided to settle here. He bought some land in Woodlawn and took up the occupation of a fisherman. He did not entirely forsake a seafaring life, however, and for two years he sailed the Great Lakes as a sailor before the mast with Captain Lindgren.

In 1869 Captain Lawson moved to beautiful Evanston, Illinois and continued the life of a fisherman, occupying a shanty near the Davis Street pier. In 1876 he married the former Petrine Wold (1855-1941) from Norway. Right after their marriage the newlyweds moved to Ludington, Michigan but by 1878 they returned to Evanston where they would remain for the rest of their lives.

On July 19, 1880 Lawrence Lawson was appointed to be the keeper, or captain of the life-saving station at Northwestern. A sailor of life-long experience, he was chosen to make seamen of the eager but inexperienced students. Just shy of his 38th birthday, he also fulfilled the requirement for "maturity" that the job required,

At first fears were expressed that an outsider would not be able to get the cooperation of the student crew and that the appointment of Lawson as captain would be the first step toward the severance of relations between the university and the life-saving station. Within a short time however, Captain Lawson, because of his superior skills as a seaman, succeeded in winning the loyalty of the crew.

George H. Tomlinson, a crew member, later recalled, "The most eventful period of the station's history began with the appointment of Captain Lawson, a veteran sailor of the seven seas, as keeper of the station. He held the post for 23 years and won the love and respect of all who entered the university in that time. As a member of one of the student crews who worked under him, I can attest to his courage, ability and fineness of character - a rare soul such as does not often come into one's life." According to Tomlinson, no one was more frequently made the subject of a character study in English classes than the revered Captain.

As time passed, Captain Lawson quickly noticed the necessity for larger quarters as his family grew and grew. In all, Captain Lawson and his wife would have eight children: Julia E. (1877-1932), Esther Marion - sometimes called Ethel (1882-1884), John Walton (1885-1968), Lawrence Oscar (1888-1890), Raymond Oliver (1891-1973), Ruth Petrine (1893-1977), Charlotte (1896-1982), and Charles W. (1900-1941).

In 1886 Captain Lawson moved the old frame shanty he had been living in at the foot of Davis Street to the lot adjoining the "Club House" a red brick building opposite the life-saving station where it then stood. Then he began construction on a new house at 1834 Sheridan Road, just across the street from the life-saving station. According to the Evanston Press of April 27, 1889, "Captain Lawson of the life saving crew. has been occupying his new residence on the drive for some time. For over three years, the Captain has been building the house with his own hands. Slowly but substantially, he has added something to it week by week until now it is really beautiful and reflects great credit upon the builder's skill and patience."

In 1886 Captain Lawson moved the old frame shanty he had been living in at the foot of Davis Street to the lot adjoining the "Club House" a red brick building opposite the life-saving station where it then stood. Then he began construction on a new house at 1834 Sheridan Road, just across the street from the life-saving station. According to the Evanston Press of April 27, 1889, "Captain Lawson of the life saving crew. has been occupying his new residence on the drive for some time. For over three years, the Captain has been building the house with his own hands. Slowly but substantially, he has added something to it week by week until now it is really beautiful and reflects great credit upon the builder's skill and patience."

Since they were subject to be called to duty at any hour, members of the student life-saving crew often lodged in the Captain's home. One crew member later recalled, "No one who has not had the privilege of waking (Captain Lawson) in the middle of the night to report some emergency could envision him coming out of his bedroom into the hall with his long white nightgown and his long graying beard, with one hand scratching his ribs, either for the answer or to help him awaken, and the other hand twisting his beard back and forth." Each crew member served a two hour watch at the life saving station, so that there was always a man on duty. In addition, the Evanston shoreline was patrolled twice each day, once just before midnight and once at dawn.

How much was someone like Captain Lawson paid by the government for overseeing the life-saving station? Official reports from 1891 listed his salary as $700.00 per year which translates to $21,672.51 in today's funds. A meager salary to be sure for someone with so much life-and-death responsibility. It was said that he supplemented his income by catching and selling fish.

During Captain Lawson's quarter century of service, the life-saving crew was responsible for the rescue of over 500 persons from the stormy waters of Lake Michigan. One such rescue occurred on the evening of May 9, 1883. A schooner, the Kate E. Howard, unloaded her cargo of lumber at the Davis Street pier in Evanston and moved three quarters if a mile into the lake for a more secure anchorage. Struck by a sudden violent squall "resembling a cyclone", the boat rolled over. The hull sank at once, but the crew managed to cling to the masts. Because of darkness, the watchman at the life-saving station knew nothing of the disaster. On bare suspicion that something was wrong, Captain Lawson ordered the surf-boat launched and pointed east. They succeeded finally in locating the wreck in time to rescue the five sailors, who were almost exhausted and quite hopeless of relief.

The most notable rescue by the crew occurred on Thanksgiving Day, 1889. The Calumet, a steam propeller ship, with 18 crew members, was driven aground near Fort Sheridan during one of the fiercest winter storms ever witnessed. According to the Calumet's chief mate, "I have been a sailor on the lake for 33 years and I want to tell you that never in all that time have I seen waves run so high as they did last night, or heard of such heroic work as that of the lifesaving crew from Evanston." This thrilling story of heroism was related in the Evanston Press of November 30, 1889: "As those seven men leaped into the icy boat, in the most fearful sea that this locality has known for years, probably few even of the spectators realized the wonderful bravery of the act...With infinite difficulty and in spite of the fearful breakers, the brawny and plucky boys, guided by their skillful captain, gradually made their way to the eighteen freezing and despairing men who were clinging to the pilot-house, the only part of the ship not swept by the waves. The captain of the ship said that they had no hope of being rescued when they saw the crew launch the boat...Three trips they made through that roaring surf, and brought every man - eighteen in all - safely to shore."

In recognition of their rescue of the Calumet crew, Captain Lawson and each member of his crew received a gold medal of honor, authorized by a special act of Congress. On the medal was inscribed: "In testimony of heroic acts in saving life from the perils of the sea."

Newspapers reported that this was the first time that every member of a lifesaving crew was awarded a medal - this honor was usually reserved to the captain of the life saving crew.

The 1890 US Census for Evanston is unfortunately lost, but we do have the Lawson family in the 1900 US Census. The family is, of course, living in the house the Captain built at 1834 Sheridan Road in Evanston. First there was 57 year old Laurence Lawson, who reported that he emigrated in 1861 and was Captain of a life saving station. Then there was his 44 year old wife Petrina who emigrated in 1863. They both reported they had been married for 23 years. Petrina reported that she had given birth to 8 children, and that 5 were still alive in 1900. The five living children in 1900 were: Julia (23), John (15), Raymond (9), Ruth (6) and Charlotte (4). As mentioned above they also reported that they had two in the life saving service living with them: 24 year old Clarence Thorne and 29 year old Edwin R. Perry. Lastly, they also had a minister living with them in 1900: 24 year old Alfred E. Harris.

On the occasion of Captain Lawson's 20th year of service in 1900, the Evanston Index noted, "The Evanston life-saving crew has made a remarkable record under the leadership of Captain Lawson during the last 20 years. It is one of the institutions that Evanstonians point to with pride, and its praises have been sung over and over again for the gallant services it has performed on different occasions. While these successes are due in large measure to the material of which the crew has been composed, those who are acquainted with its methods are quick to give the credit to the captain. He has been faithful and active and at all times of a disposition that commanded the respect of the students who were associated with him. this popularity has given to him the hold he has held upon them. To it is attributable the remarkable performances that have been accomplished under his leadership."

In 1902 the Chicago Tribune noted that "while railroads and labor unions are considering the "age limit" problem, there is a man in Evanston who works hard at 60. He is Captain Lawrence O. Lawson of the Evanston life-saving crew." But trouble was on the horizon for Captain Lawson.

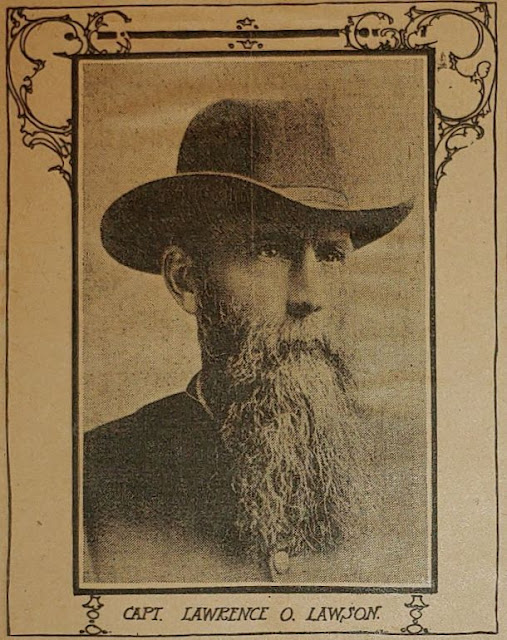

The Chicago Inter-Ocean reported about the problem on April 4, 1903 under this portrait if Captain Lawson:

As is usually the case with the truly great who never seek out fame, Captain Lawson was not mentioned again in the newspapers until he died in the home he built at 1834 Sheridan Road on October 30, 1912:

In recognition of their rescue of the Calumet crew, Captain Lawson and each member of his crew received a gold medal of honor, authorized by a special act of Congress. On the medal was inscribed: "In testimony of heroic acts in saving life from the perils of the sea."

Newspapers reported that this was the first time that every member of a lifesaving crew was awarded a medal - this honor was usually reserved to the captain of the life saving crew.

The 1890 US Census for Evanston is unfortunately lost, but we do have the Lawson family in the 1900 US Census. The family is, of course, living in the house the Captain built at 1834 Sheridan Road in Evanston. First there was 57 year old Laurence Lawson, who reported that he emigrated in 1861 and was Captain of a life saving station. Then there was his 44 year old wife Petrina who emigrated in 1863. They both reported they had been married for 23 years. Petrina reported that she had given birth to 8 children, and that 5 were still alive in 1900. The five living children in 1900 were: Julia (23), John (15), Raymond (9), Ruth (6) and Charlotte (4). As mentioned above they also reported that they had two in the life saving service living with them: 24 year old Clarence Thorne and 29 year old Edwin R. Perry. Lastly, they also had a minister living with them in 1900: 24 year old Alfred E. Harris.

On the occasion of Captain Lawson's 20th year of service in 1900, the Evanston Index noted, "The Evanston life-saving crew has made a remarkable record under the leadership of Captain Lawson during the last 20 years. It is one of the institutions that Evanstonians point to with pride, and its praises have been sung over and over again for the gallant services it has performed on different occasions. While these successes are due in large measure to the material of which the crew has been composed, those who are acquainted with its methods are quick to give the credit to the captain. He has been faithful and active and at all times of a disposition that commanded the respect of the students who were associated with him. this popularity has given to him the hold he has held upon them. To it is attributable the remarkable performances that have been accomplished under his leadership."

In 1902 the Chicago Tribune noted that "while railroads and labor unions are considering the "age limit" problem, there is a man in Evanston who works hard at 60. He is Captain Lawrence O. Lawson of the Evanston life-saving crew." But trouble was on the horizon for Captain Lawson.

The Chicago Inter-Ocean reported about the problem on April 4, 1903 under this portrait if Captain Lawson:

VETERAN CHIEF OF EVANSTON LIFE-SAVING CREW

Hoary-headed and storm beaten, but still sinewy and agile and as efficient in the rescue of human life as in his younger days, Captain Lawrence O. Lawson of the Evanston life-saving crew, is awaiting the announcement of his retirement from the service on account of a slight defect in eyesight. As anxious as the Captain himself are the citizens of Evanston, who think with regret of the prospect of the sturdy old seaman's removal. Familiar with the veteran life-saver's marvelous record during his thirty years of service at the Evanston station, they are urging upon the department at Washington the desirability of his retention, in spite of his failure to pass every test in the recent examination. Captain Lawson himself is eager to remain at the post he has held so long and declares that he is able to fulfill his duties now as well as ever. Since he took charge of the Evanston station in 1880 not a single life has been lost along that coast. All told, he and his crew have rescued 500 people from the lake. In 1889, the year of the Calumet disaster, 101 men and women were saved by Captain Lawson's men. For this unparalleled record the captain wears the coveted gold medal, presented only in cases or extraordinary merit.

In their Sunday April 12, 1903 edition, the Chicago Inter Ocean outlined more of what was going on with the matter of Captain Lawson:

The unfeeling machinery of civil service is about to retire another hero from the nation's roll of workers.

For twenty-five years, Captain Lawrence O. Lawson of Evanston has faithfully watched one of the outposts of the life-saving service. Only a few less than 500 lives for as records of his vigilance and bravery. Forty-seven athletic built young men in different parts of the country, and of all professions from the ministry to the stage, revere him as the molder of their habits of devotion to duty and self-sacrifice.

These count for nothing with the civil-service machinery. This worker, who had grown old in the service, is as brave as ever, as ready to dive into the lake and rescue a swimmer or pull an oar as the surf boats cuts through the breakers to a wreck. His judgment is unimpaired, but his eyes have grown old. He can still see as far across Lake Michigan; the binoculars reveal as much as they ever did over the watery expanse, and the signal lights sign as brightly to him as they did a quarter of a century ago. But he could not pass the optical test. The test letters on a white card were occasionally blurred to the eyes of the old mariner.

It is a critical weakness. Can a man rescue drowning men and women or guide a surf boat through the darkness to a foundering vessel if he cannot pass the test which is undergone in the rear room of a jewelry store, amid an order of varnish and watchmakers oil. This is the question that the government civil-service answers negatively.

All of the plaudits and shows of support came to naught when on July 1, 1903 the government announced that effective immediately, 30 year old Patrick Murray would be the new captain of the Evanston life-saving crew. The gold-medal career of Captain Lawrence O. Lawson was over.

After the Captain's retirement, William E. McClennan, a member of the crew from 1882 to 1885 remarked, "His 23 years of service have in themselves demonstrated his marked ability, courage, faithfulness and extraordinary resourcefulness. he has never been know to give up the most forlorn hope so long as human lives were in danger. It is doubtful whether the annals of life-saving will reveal a more resourceful and masterful mind than that of Captain Lawson. Denied the advantages of a technical education, he is nevertheless a great man -- and as good as he is great. Without him as a leader through almost a quarter of a century, the Evanston life-saving crew could hardly have won for itself much more than average fame."

As is usually the case with the truly great who never seek out fame, Captain Lawson was not mentioned again in the newspapers until he died in the home he built at 1834 Sheridan Road on October 30, 1912:

As mentioned, Captain Lawson was buried at Graceland Cemetery. He is in the Knolls Section, Lot 69, Space 1.

When I started this article I was under the impression that Captain Lawrence Lawson had been virtually forgotten today. That is partially true. After Lawson's house was razed by Northwestern, there was a move to name the small park next to Lighthouse Beach after the Captain. Lawson Park was dedicated July 10, 1988:

When I started this article I was under the impression that Captain Lawrence Lawson had been virtually forgotten today. That is partially true. After Lawson's house was razed by Northwestern, there was a move to name the small park next to Lighthouse Beach after the Captain. Lawson Park was dedicated July 10, 1988:

It looked a little more bleak when I visited on February 27, 2020:

The park dedicated to Captain Lawson was a nice idea, but nowhere in the park is there anything that says who Captain Lawson was, or why a park on the lakeshore was named after him. In fact, the name "Lawson Park" does not even specify which Lawson the park is named for.

Captain Lawrence O. Lawson was not forgotten however, by the US Coast Guard. Here are some photos of the United States Fast Response Cutter Lawrence Lawson, commissioned March 18, 2017:

May he rest in peace.

Special thanks to Evanston historian extraordinaire Mike Kelly who provided much of the material for this article.

Thanks also to Ron Sims who provided the following two photos:

The first is an aerial view of Northwestern University Evanston Campus, circa 1907. The lifesaving station is on the lower right.

The second photo shows the lifesaving station in the shadow of Fisk Hall in 1910. The lifesaving station was originally on the site of Fisk Hall and moved further south when Fisk Hall was built. Photo is from the following source:Chicago: Its History and Its Builders [ed. by] J Seymour Currey. Chicago, S J Clarke, 1912. Vol. 2, plate laid in btw 350-351.

Captain Lawrence O. Lawson was not forgotten however, by the US Coast Guard. Here are some photos of the United States Fast Response Cutter Lawrence Lawson, commissioned March 18, 2017:

The Lawson's crew members were heavily involved in the creation of her seal, researching her namesake and incorporating Keeper Lawrence O. Lawson’s brave actions into the seal. For example, the shield on the seal is purple and white, the colors of Northwestern University, representing Lawson and his heroic student volunteer crew from Northwestern. This is just one of many aspects of the seal that symbolize the harsh yet successful rescue on that Thanksgiving Day.

Here's what the Coast Guard has to say about Captain Lawson:

Named for a Hero

The new cutter’s name is attributed to U.S. Lifesaving Service Station Keeper Lawrence O. Lawson, keeper of the Evanston, Ill. Lifeboat Station. Lawson and his crew gained notoriety for rescuing the 18-person crew of the Calumet on Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 28, 1889, as the steam vessel was in distress during a raging storm on Lake Michigan. Lawson and his crew, made up entirely of volunteer students from nearby Northwestern University, navigated through 15 miles of blizzard-like weather by train, horseback and foot. They attempted to fire a line to the vessel but failed twice, then decided to launch a surfboat. The crew was finally able to launch in the near-impossible icy conditions, and recused all 18 members of the Calumet after three successive trips. Lawson and his crew’s actions did not go unnoticed, as they received the Gold Lifesaving Medal for their heroic actions that day. Cape May’s newest FRC is named for a true hero.

It is appropriate that Lawrence Lawson is still saving lives on the water.

So now you know the story of one of Evanston's true heroes, Captain Lawrence O. Lawson, who rescued over 500 souls from the treacherous waters of Lake Michigan, no matter what the weather or peril to himself.

Special thanks to Evanston historian extraordinaire Mike Kelly who provided much of the material for this article.

Thanks also to Ron Sims who provided the following two photos:

This photo is from the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/ item/2007663913/

No comments:

Post a Comment