We will end our look at the life and career of noted sculptor Leonard Wells Volk by looking at the works he is most famous for: the life mask and hands of Abraham Lincoln.

After Leonard Volk’s death, the Chicago Daily Tribune printed an article called “An Afternoon with Leonard Volk” where Volk describes the story of the Lincoln mask. Here’s the article by Annie Hungerford:

During the winter of 1891 and 1892, when things were beginning to crystalize for the World’s Fair, I chanced upon the name of Leonard W. Volk on a studio in the Athenaeum Building. It was almost a forgotten acquaintance, for I had known him prior to the Chicago Fire, but before being admitted and introducing myself, the embers of the old acquaintance were quickly rekindled into the glow of friendship.

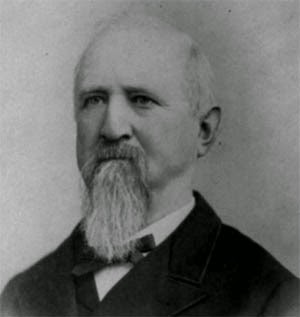

I recall him now, as he stood hale and erect, attired in the long atelier coat used by sculptors – the flecks of plaster on it suggestive of modeling tools, and the little black velvet cap beloved of artists; and wearing his sixty-odd years like the “Pastor” in Wilhelm Meiter, “not a burden on his back but a crown of glory on his head.” A rugged figure among the rugged faces about his studio. For his work, like himself, bore the impress of a man. Full of force, everything Mr. Volk did or said was replete with independent thought. He was never touched by the conventionality and scholasticism of the French school of art, but in his broad Americanism and westernism was preeminently the historic sculptor of a decisive epoch in the history of a great nation.

With keen sense of humor and love of anecdote, surrounded by the effigies of great men, and every one a friend, he recounted stories of Lincoln and Douglas, whom he had known as well.

“And here”, he said, pointing to a wooden armchair of generous proportions, dull red in color and well worn, “is the chair where Lincoln sat when I modeled his bust.”

Several years before in New York, the Irish sculptor, Mr. O’Donovan, had called my attention to three things in the Metropolitan Museum. An original “Lucca Della Robia,” a statue group, “The Death of Abel,” and the life mask of Lincoln by Leonard W. Volk. He told me that the original life mask was owned by Mr. Douglas Volk, the artist son of the sculptor – then resident in New York, but that the replica was in the museum. I wondered that Mr. Volk could part with so precious a relic during his lifetime. But after learning of his art losses during the “great fire” wonder ceased that he should choose a less inflammable environment for an article of national interest. I give Mr. Volk’s own accounting of the modeling of the life mask and bust. Brief and sketchy as it is it shows that Mr. Volk’s word pictures are as vigorous as his modeling. Speaking of Lincoln:

“My studio was in the fifth story and there were no elevators in those days, and I soon learned to distinguish his step on the stairs and sure he came up two if not three steps at a stride. When he sat down the first time in that hard, wooden, low-armed chair, which had been occupied by Douglas, Seward, and Gens. Grant and Dix, he said: ‘Mr. Volk, I never sat before to sculptor or painter-only for daguerreotypes and photographs. What shall I do?”

I told him I would only take the measurements of his head and shoulders that time, and next morning, Saturday, I would make a cast of his face, which would save him a number of sittings. He stood up against the wall and I made a mark above his head, and then measured up to it from the floor and said, “You are just twelve inches taller than Judge Douglas, that is, six feet one inch.” Before commencing the cast next morning, and knowing Mr. Lincoln’s fondness for a story, I told one in order to remove what I thought an apprehensive expression – as though he feared the operation might be dangerous, and this is the story: I occasionally employed a little back eyed, black haired, dark skinned Italian as a formatore in plaster work, who had related to me a short time before that himself and a comrade image-vender were ‘doing’ Switzerland by hawking their images. One day a Swiss gentleman asked him if he could make his likeness ‘Mat’ said he took special pains to some plaster, laid the big Swiss gentleman on his back, stuck a quill in each nostril for him to breathe through, and requested him to close his eyes. Then ‘Mat” as I called him, poured the soft plaster all over his face and forehead; then he paused for reflection; as the plaster began to set he became frightened, as he had never before undertaken such a job, and had neglected to prepare the face properly, especially the gentleman’s huge beard, mustache, and the hair about the temples and forehead, through which, of course, the plaster had run and become solid. Mat made an excuse to go outside the door-“then,” said he, “I run like -----.”

“I saw Mr. Lincoln’s eyes twinkle with mirth. ‘How did he get it off?’ said he. I answered that probably after reasonable waiting for the sculptor, he had to break it off and cut and pull out all the hair which the tenacious plaster touched the best way he could. ‘Mat’ said he took special pains to avoid that particular part of Switzerland after that artistic experience. But his companion, who somewhat resembled him, not knowing anything of his partner’s performance, was soon after overhauled by the gentleman and nearly cudgeled to death.

“Upon hearing this tears actually trickled down Mr. Lincoln’s bronzed cheeks, and he was at once in the best of humors. He sat naturally in the chair when I made the cast, and saw every move I made in a mirror opposite, as I put the plaster on without interference with his eyesight or his free breathing through the nostrils. It was about an hour before the mold was ready to be removed, and being all in one piece, with both ears perfectly taken, it clung pretty hard, as the cheek bones were higher than the jaws at the lobe of the ear. He bent his head low and took hold of the mold, and gradually worked it off without breaking or injury; it hurt a little as a few hairs of the tender temples pulled out with the plaster, and made his eyes water, but the remembrance of the poor Swiss gentleman evidently kept him in good humor.

“The last sitting was given Thursday morning, and I noticed that Mr. Lincoln was in something of a hurry. I had finished the head, but desired to represent his breast and brawny shoulders as nature presented them; he stripped off his cost, waistcoat, shirt, cravat, and collar, threw them on a chair, pulled his undershirt down a short distance tying the sleeves behind him, and stood up without a murmur for an hour or so. I then said that I was done, and was a thousand times obliged to him for his promptness and patience, and offered to assist him to redress, but he said, ‘No, I can do it better alone.’ I kept at my work without looking toward him, wishing to catch the form as accurately as possible while it was fresh in my memory.

“Mr. Lincoln left hurriedly, saying he had an engagement, and with a cordial ‘Goodbye! I will see you again soon,’ passed out. A few moments after I recognized his steps rapidly returning. The door opened and he came in, exclaiming: Mr. Volk! I got down on the sidewalk and found I had forgotten to put on my undershirt and thought it wouldn’t do to go through the streets this way.’

“Sure enough, there were the sleeves of that garment dangling below the skirts of his broadcloth frock coat! I went at once to his assistance and helped to undress and redress him all right, and out he went with a hearty laugh at the absurdity of the thing.”

He lifted the replica to show it in a better light. The strong, firm face of Lincoln, rough hewn, almost distinguished in its homeliness, with its tenderness and humor and pathos well defined; one looked upon it with reverence as the Israelites must have done when Moses came down from the mountain and “wist not that his face shone.”

|

| Lincoln Life Mask by Leonard Wells Volk |

And the hands of Lincoln that he modeled the day after his nomination at the “Wigwam,” so strong and constructive, all that the face failed to tell of patient wrestling with destiny is brought out in that conscious hand that hold the destiny of nations in its grasp. But I will let the sculptor’s words again tell the story.

“By previous appointment I was to cast Mr. Lincoln’s hands the Sunday following the memorable Saturday at 9 a.m. I found him ready, but he looked more grave and serious than he had appeared on the previous days. I wished him to hold something in his right hand, and he looked for a piece of pasteboard, but could find none. I told him a round stick would do as well as anything. Thereupon he went to the woodshed, and I heard the saw go, and he soon returned to the dining-room (where I did the work) whittling off the end of a piece of broom handle. I remarked to him that he need not whittle off the edges.

“’O, well,’ said he, ‘I thought I would like to have it nice.’

“When I had successfully cast the mold of the right hand I began the left, pausing in a few moments to hear Mr. Lincoln tell me about a scar on his thumb.

“’You have heard that they call me a rail-splitter, and you saw them carrying rails in the procession Saturday evening; well, it is true that I did split rails, and one day, while I was sharpening a wedge on a log, the ax glanced and nearly took my thumb off, and there is the scar, you see.’

“The right hand appeared swollen as compared with the left on account of excessive handshaking the evening before; this difference is distinctly shown in the cast.

“That Sunday evening I returned to Chicago with the molds of his hands, three photographic negatives of him, the identical black alpaca campaign suit of 1858, and a pair of Lynn newly-made pegged boots. The clothes were all burned up in the great Chicago fire. The cast of the face and hands I saved by taking them with me to Rome, and they have crossed the sea four times.

“The last time I saw Mr. Lincoln was in January, 1861, at his home in Springfield. His little parlour was full of friends and politicians. He introduced me to them all, and remarked to me aside that since he had sat for me for his bust he had lost forty pounds in weight. This was easily perceptible, for the lines of his jaws were sharply defined through the short beard which he was allowing to grow. Then he turned to the company and announced in a general way that I had made a bust of him before his nomination and that he was then giving daily sittings at the St. Nicholas Hotel to another sculptor; that he had sat for him for a week or more but could not see the likeness, though he might yet bring it out.

“’But,’ continued Mr. Lincoln, ‘in two or three days after Mr. Volk commenced my bust there was the animal himself.’

“And this was about the last, if not the last, remark I ever heard him utter, except the good-by and good wishes for my success.”

In the development of art, whether in the individual or in the state, the first instinct leads to portraiture-the personation of an individual. It precedes the ideal. Let a man attain wealth and straightway he has his own or his wife’s picture painted. To the next generation these become valuable as historic of the family life, or they are at least valuable as curios, although it is maintained that “the necessity of one generation becomes the art of the next.”

Then comes the ideal; no more portraits, but beautiful madonnas, and romance pictures, the genre, the dramatic in art, the picture with a story. Then as civilization advances we again find the portrait, but this time idealized, and it is added to the romance gallery.

As in the baronial halls of England stately lords and ladies look down upon their progeny painted by the Reynolds and Van Dykes. It was the primary love of portraiture which inspired Mr. Volk. He scarcely attempted the ideal.

Born at a time and into an environment where the practical lessons of life prevailed, setting in a State which from its topography was forced to deal with national issues, Mr. Volk was caught in the political vortex and it influenced his art from the first.

He could not model “The Sleep of the Flowers” like Mr. Tatt, nor the “Staying of the Sculptor’s Hand,” like Mr. French, nor animals like Mr. Kormys, nor allegorical groups like Mr. Bitter; “not things but men” was essentially his motto. And his service as the historic portrait sculptor of his time cannot be estimated.

His fidelity, his realism, his insight are of the greatest value. As an artist of ideality and originality, or of brilliant technique, Mr. Volk did not take the front rank. He was born too soon for that. But as a man keenly alive to the impressions of the hour, full of realism, faithful in detail, there are few his equal.

Apart from historic value his work will never be great, except the statue of Douglas at Woodland Park. But the beauty of that monument is rarely equated.

From his breezy attitude, “The Little Giant” is a graceful and eloquent tribute to the genius of his friend.

The rays of the setting sun mellowed the light of the studio and fell on the sculptor before I left on that winter afternoon.

So an earnest and noble life has passed on, leaving his land and his art richer for having lived.

The 1880 US Census shows the Volks living at 36 (now 634) East 35th Street in Chicago, a stone's throw away from the Stephen A. Douglas tomb. It is only Leonard, his wife and Nora living in the family home now; Stephen has moved out to seek his fortune. The financial picture for the Volks must have improved - they now have a live-in servant, twenty two year old Augusta Meyer.

Emma Clarissa Barlow Volk died May 28, 1895. She was sixty one years old. The Chicago Daily Tribune of May 31, 1895 carried the following notice:

Readers of the Chicago Daily Tribune of August 20, 1895 saw the following story:

Leonard W. Volk, the sculptor, died suddenly at the Hotel Cascade in Osceola, Wis. at 9 o'clock yesterday morning of heart trouble.

Mr. Volk was remarkably well preserved for a man of his years and walked as strong and erect as a youth of 20. He was in the habit of spending the summer months in Wisconsin. He went away a little earlier than usual this year, and his friends in Chicago had no intimation that he was ill until word of his death came.

"Father died very suddenly," said Mrs. Nora Volk Colt, his daughter. "He had been failing, it is true ever since mother died in May but we supposed he had begun to improve and would be himself again. Six weeks ago he went to Osceola, Wis., his usual summer resort. At that time he is morning we received a dispatch stating that he had died very suddenly. We have none of the particulars of his death, but believe he must have died from heart failure.

Here is his death notice from the Chicago Daily Tribune:

and here is an article about his funeral from the Tribune of August 22, 1895:

I cannot emphasize enough that I have hardly scratched the surface of the life and works of Leonard Volk in this article. There is a tremendous amount of information available on the internet, and Volk's family papers reside at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. I am surprised that to date no one has written a biography of Volk. I wish I had the time, because Volk is a fascinating subject.

Leonard Wells Volk, a gifted sculptor who breathed life into cold stone - may he rest in peace.

LEONARD VOLK DEAD

News of the Sculptor's Demise Reaches Chicago

Leonard W. Volk, the sculptor, died suddenly at the Hotel Cascade in Osceola, Wis. at 9 o'clock yesterday morning of heart trouble.

Mr. Volk was remarkably well preserved for a man of his years and walked as strong and erect as a youth of 20. He was in the habit of spending the summer months in Wisconsin. He went away a little earlier than usual this year, and his friends in Chicago had no intimation that he was ill until word of his death came.

"Father died very suddenly," said Mrs. Nora Volk Colt, his daughter. "He had been failing, it is true ever since mother died in May but we supposed he had begun to improve and would be himself again. Six weeks ago he went to Osceola, Wis., his usual summer resort. At that time he is morning we received a dispatch stating that he had died very suddenly. We have none of the particulars of his death, but believe he must have died from heart failure.

Here is his death notice from the Chicago Daily Tribune:

and here is an article about his funeral from the Tribune of August 22, 1895:

Leonard Volk is buried in Rosehill Cemetery in Chicago, the site of so many of his works of art. Volk's monument is a unique study of a unique man:

When Volk knew that his death would not be far off, he designed what he felt was a fitting tombstone. The monument itself was actually executed by the Gast Monument Company of Chicago, a company known to have created many unique tombstones throughout Chicagoland.

I cannot emphasize enough that I have hardly scratched the surface of the life and works of Leonard Volk in this article. There is a tremendous amount of information available on the internet, and Volk's family papers reside at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. I am surprised that to date no one has written a biography of Volk. I wish I had the time, because Volk is a fascinating subject.

Leonard Wells Volk, a gifted sculptor who breathed life into cold stone - may he rest in peace.

Great series, Jim! Maybe when you retire, you can write that biography - you have a good start on it!

ReplyDelete